Introduction: Just How Big Was He?

Source: Refreshment stand on US highway 99 in Oregon, Dorothea Lange, Wikimedia Commons

Let’s pretend for a minute that you have an adventure on the way home from school. You are chased by a rather large dog who seems really hungry and grouchy. You run in the house, slam the door, and begin to tell your mom about your scary walk (or run) home from school.

You begin by telling her that it was a big dog. She asks how big, and you reply “I don’t know; it was just big.” She asks again “How big?” You get really frustrated because that’s not really the point, and she’s preventing you from getting to the really good part of the story. What your mom is asking for is some help visualizing the dog that was chasing you. She wasn’t there, so she wants you to add some more description to help her get a picture in her mind. When writers add details to help readers form mental pictures, they are using a stylistic device called imagery. Good writers and good story tellers do this by adding figurative language to their descriptions to help readers or listeners form images in their minds. Let’s go back to the story now.

Your mom asks you how big the dog was, and you tell her that it was exactly 36 inches tall and weighed 70 pounds.

Do you really do this? Of course not because for one thing, you don’t know the dog’s height and weight for sure, and besides, do those figures really give her a sense of how big and mean the dog was? So here’s what you do. You use a figure of speech. You could use a simile and say that the dog was like Mr. Green’s mastiff at the end of the block. She then gets a picture in her head of the giant dog at the end of the block, and that helps her understand the significance of your adventure.

You could also use a metaphor and say that the dog was Cerberus; here you’re saying that the dog was the three-headed dog who guarded Hades. This might seem to your mother to be hyperbole—an exaggeration. However, any of these descriptions help your mom picture the dog chasing you down the street and therefore make her a lot more interested in your story and worried about your safety.

Does this discussion about figurative language sound familiar? If it does, that’s because you are probably used to identifying and understanding similes and metaphors in your reading. You know that when you borrow language from one part of life and use it in another, you are using figures of speech. When writers use figurative language, they are trying to help the reader understand better by comparing whatever it is they are talking about to something with which the reader is familiar.

For a quick review, see if you can guess the word that fills in the blank and matches the picture. Click on the button to check your answer. The word and how it’s used figuratively will appear.

Image sources:

Baby Photograph, Fenja1, Palnatoke, Wikimedia Commons

Chocolate Hills, Bohol, Philippines, Wikimedia Commons

Gayot Atlas Statistique, Eugene Gayot, Wikimedia Commons

Walking pig, Joseph Martin Kronheim, Project Gutenberg

Blackstrap Molasses, Badagnani,Wikimedia Commons

The sentences above show the difference between literal and figurative language. We use what we know about the comparison word or phrase and all of its meanings to help us understand the speaker or writer. Do all babies sleep soundly every single night? No, but we understand what it means to sleep as soundly as a baby without a care in the world, and that comparison is so much more interesting than saying that you slept eight hours without waking up. The comparison adds another layer of meaning that further explains how well you slept. How old are the hills anyway? They are probably older than the joke your teacher told you, but it sounds better to suggest that he told a joke that was thousands of years old. That comparison adds the suggestion that he is really old-fashioned and out of touch.

Could you really eat an entire horse? Of course not, but it’s so much more effective to say that rather than “I’m so hungry I know I can eat an appetizer, main course, and a dessert.” We don’t really know whether pigs eat a lot, but we’ve always heard they do, and by saying that you became one by eating a lot, you give that thought meaning beyond just saying that you ate a big meal. What is molasses, and why is it slow? It’s a thick, strong-tasting syrup that takes a long time to drip from a spoon or pour from a bottle. Can you see how figures of speech spice up our conversations and our writing and make them more specific?

For fun, try keeping a journal for an entire day noting each time you hear or use figures of speech like the ones above.

In the rest of the lesson, we will learn about some new figures of speech—personification, hyperbole, and refrains—and see how writers use them to add meaning to their writing.

Personification, Hyperbole, and Refrain

Personification

Source: A Frog He Would A Wooing Go, Charles. H. Bennett, Project Gutenberg

Now let’s look at some other specific kinds of figures of speech, beginning with personification. First, take a close look at the word. Do you see a root word in there somewhere? Yes, person is part of the word “personification”, and it is there for a very good reason: Personification simply means making non-persons (e.g., trees, animals, objects) act like people. In the picture above, the toad and the mouse appear to be standing on two legs instead of four, talking to one another, and generally carrying on as if they were human beings.

Personification is easy to identify when you’re reading about animals because you tend to think of them like humans. It gets harder when we see examples of personification that don’t have to do with animals but with other living things or inanimate objects. See if you can find the examples of personification in the paragraph below.

Do you see how personification helps you form images in your mind? Those images then help you have a better understanding of what the writer is saying.

Hyperbole

“Hyperbole” (pronounced hy-PER-bo-le) is perhaps an unfamiliar word, but it has a simple meaning: exaggeration! Click on this video to see a few musical examples of hyperbole.

Source: Hyperbole, Bill MacDonald, Flick

Hyperbole has been used throughout literature for many centuries to add drama or comedy to situations. Modern tall tales make use of hyperbole to exaggerate the feats and characteristics of their main characters. For example, the American tall tale about Paul Bunyan relies heavily on hyperbole to establish Bunyan’s giant stature and abilities.

Hyperbole is also frequently used in comedy to offer a humorous description of somebody or something. In the cartoons about Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner, the road runner always treats the poor coyote to a trick that involves hyperbole: an enormous lead weight falling on him or enough dynamite to blow up more than just one coyote!

The fields of advertising and propaganda use hyperbole almost exclusively, which has led to its having a somewhat negative connotation. Typically, advertisers use hyperbole to exaggerate the benefits or claims of their products to boost sales and to add to the image and popularity of whatever they are advertising. The modern term “hype” is a shortened derivation of the term.

Take a minute to think about a product you’ve seen advertised lately. Does it contain hyperbole or “hype”?

Click the box below to see an example.

Here are some common examples of hyperbole:

I could eat a horse. (Remember that one from above?)

If I can’t get that new iPod, I will surely die.

I have a ton of homework tonight.

My mom complained that she had a million things to do.

Refrain

Refrain is a device authors use to enhance meaning. Refrains can be found in prose, but more frequently, refrains are used in music and poetry. Have you ever heard a song on the radio and been unable to get it out of your head? Most likely it was because of the chorus (the phrase repeated over and over again between verses of lyrics).

Ever wonder why popular music relies so heavily on refrains (choruses)? Song writers use this device to make songs easy to remember and catchy. Poets sometimes use refrains for the same reason: to make their point noticeable and memorable.

Here are two examples of refrains. The two examples are incomplete texts, but the refrains are in bold.

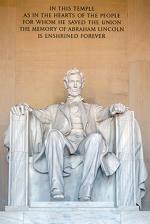

Excerpt from “O Captain! My Captain!” by Walt Whitman

O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done,

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won,

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the steady keel, the vessel grim and daring;

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up—for you the flag is flung—for you the bugle trills,

For you bouquets and ribbon’d wreaths—for you the shores a-crowding,

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning;

Here Captain! dear father!

This arm beneath your head!

It is some dream that on the deck,

You’ve fallen cold and dead.

If you continue to the third stanza, you will see the refrain "Fallen cold and dead" repeated again. You can read the complete poem, "O Captain! My Captain," on The Poetry Foundation website.

Source: Poe Corbeau, Caton, Wikimedia Commons

Excerpt from “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore . . .

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly . . .

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as "Nevermore." . . .

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before." . . .

Then the bird said "Nevermore."

“The Raven” is one of the best examples of the use of refrain in poetry. Eleven of the poem’s 18 stanzas end with the word “nevermore,” and the other seven stanzas end with either “more” or “evermore.” If you would like to read the entire poem, visit The Poetry Foundation.

How and Why Authors Use Personification, Hyperbole, and Refrain

Source: Hey Diddle Diddle, Fennec, Wikimedia Commons

Now that you are familiar with personification, hyperbole, and refrain, let’s see how authors use these devices to achieve their purposes.

Personification

Source: Wolf, Dick Hartley, Project

Gutenberg

We now know that personification is a device that writers use to give nonhuman things human qualities so that readers can relate to what authors are saying. Personification connects readers with the object that is personified. Personification can make descriptions of nonhuman entities more vivid or can help readers understand, sympathize with, or react emotionally to nonhuman characters. Let’s look at a short poem by Jack Prelutsky called “A Wolf Is at the Laundromat.” As you read, write down every time you see an example of personification.

When you have finished, click below to see a few examples.

Now that you’ve identified all the examples of personification in this funny little poem, can you think about why the poet might have personified a wolf in this way? What do you the reader understand about this particular wolf because of the way the poet used personification? You might want to take a minute to jot down a few thoughts. When you finish, click below to see a sample response.

Source: Tory Refugees by Howard Pyle,

Howard Pyle, Wikimedia Commons

Hyperbole

Now, read the following excerpt from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “A Concord Hymn,” written in 1837 to honor the great Battle of Concord during the Revolutionary War. Here, the author uses hyperbole to make a dramatic, important point.

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April's breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.

Refrain

Remember, refrain is a device writers use when they want to repeat verses or phrases for emphasis, usually at the end of a stanza. Read the following poem and note the use of a refrain.

The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls

By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Source: Isle of Shoals, Childe Hassam, Wikimedia Commons

The tide rises, the tide falls,

The twilight darkens, the curlew calls;

Along the sea-sands damp and brown

The traveller hastens toward the town,

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

Darkness settles on roofs and walls,

But the sea, the sea in the darkness calls;

The little waves, with their soft, white hands,

Efface the footprints in the sands,

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

The morning breaks; the steeds in their stalls

Stamp and neigh, as the hostler calls;

The day returns, but nevermore

Returns the traveller to the shore,

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

Can you see why the refrain is so effective in this poem? What does the idea of the recurring tides have to do with the overall meaning of the poem? When you think you have an answer, click below for a sample response.

Your Turn

Now that you know more about personification, hyperbole, simile, and metaphor, read the following excerpt. Stop when you get to a highlighted word or group of words. Decide what figure of speech it is and why you think the author, Louisa May Alcott, used it. What is the effect of that particular figurative language? After thinking about it and coming up with your own ideas, click on the interactive below the excerpt to see possible responses.

Excerpt from Eight Cousins by Louisa May Alcott

Rose has been sent to live with two elderly aunts, Peace and Plenty, after the death of her parents. Here she is feeling very lonely and sad.

Rose sat all alone in the big best parlor, with her little handkerchief laid ready to catch the first tear, for she was thinking of her troubles, and a shower was expected. She had retired to this room as a good place in which to be miserable; for it was dark and still, full of ancient furniture, sombre curtains, and hung all around with portraits of solemn old gentlemen in wigs, severe-nosed ladies in top-heavy caps, and staring children in little bob-tailed coats or short-waisted frocks. It was an excellent place for woe; and the fitful spring rain that pattered on the window-pane seemed to sob, "Cry away: I'm with you."

Rose really did have some cause to be sad; for she had no mother, and had lately lost her father also, which left her no home but this with her great-aunts. She had been with them only a week, and, though the dear old ladies had tried their best to make her happy, they had not succeeded very well, for she was unlike any child they had ever seen, and they felt very much as if they had the care of a low-spirited butterfly.

They had given her the freedom of the house, and for a day or two she had amused herself roaming all over it, for it was a capital old mansion, and was full of all manner of odd nooks, charming rooms, and mysterious passages. Windows broke out in unexpected places, little balconies overhung the garden most romantically, and there was a long upper hall full of curiosities from all parts of the world; for the Campbells had been sea-captains for generations.

Then both old ladies put their heads together and picked out the model child of the neighbourhood to come and play with their niece. But Ariadne Blish was the worst failure of all, for Rose could not bear the sight of her, and said she was so like a wax doll she longed to give her a pinch and see if she would squeak. So prim little Ariadne was sent home, and the exhausted aunties left Rose to her own devices for a day or two.

Bad weather and a cold kept her in-doors, and she spent most of her time in the library where her father's books were stored. Here she read a great deal, cried a little, and dreamed many of the innocent bright dreams in which imaginative children find such comfort and delight. This suited her better than anything else, but it was not good for her, and she grew pale, heavy-eyed and listless, though Aunt Plenty gave her iron enough to make a cooking-stove, and Aunt Peace petted her like a poodle.

Before she had time to squeeze out a single tear a sound broke the stillness, making her prick up her ears. It was only the soft twitter of a bird, but it seemed to be a peculiarly gifted bird, for while she listened the soft twitter changed to a lively whistle, then a trill, a coo, a chirp, and ended in a musical mixture of all the notes, as if the bird burst out laughing. Rose laughed also, and, forgetting her woes, jumped up.

Rose discovers that there is a young maid in the house who is making the bird noises. They visit with each other, and the maid asks Rose where she has been:

"Oh, dear me, yes! I've been at boarding school nearly a year, and I'm almost dead with lessons. The more I got, the more Miss Power gave me, and I was so miserable that I 'most cried my eyes out. Papa never gave me hard things to do, and he always taught me so pleasantly I loved to study. Oh, we were so happy and so fond of one another! But now he is gone, and I am left all alone."

The tear that would not come when Rose sat waiting for it came now of its own accord two of them in fact and rolled down her cheeks, telling the tale of love and sorrow better than any words could do it.

Resources

Resources Used in This Lesson: Bibliography

Alcott, Louisa May. Eight Cousins. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2726/2726-h/2726-h.htm.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Concord Hymn.” Poetry Foundation. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/175140.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. “The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls.” Poetry Foundation. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173917.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Raven.” Poetry Foundation. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/178713.

Prelutsky, Jack. “A Wolf Is at the Laundromat.” Poetry Foundation. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/177564.

Whitman, Walt. “O Captain! My Captain!” Leaves of Grass. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.