Introduction

In the lesson Writing an Engaging Short Story with Well-Developed Conflict and Resolution, the short story was defined as “an invented prose narrative shorter than a novel.” However, knowing the length of something is of limited use when you’re at the keyboard searching for inspiration. We aren’t going to redefine a short story, but knowing the genre from another perspective may help you write in it. The metaphor below has added to many students’ understanding and aided them in final revisions. Consider this comparison:

A novel is a house where the reader is invited to explore every room, right down to snooping in the closets. Novels are discursive (expansive) and apt to take side trips. A short story is a single room in the house that invites the reader to lean in through the open window and see what's happening in one room.

—Kate Wilhelm, science fiction author

Every stage of writing a short story is a formidable challenge. In earlier lessons, you have plotted, profiled, and drafted a story. If not, your teacher has probably explained those parts of the short story writing process. In this lesson, you will need to have drafted a short story as you learn how to revise and tighten your draft by eliminating side trips and incorporating some of the literary strategies that the masters of the genre have used. You will improve your story by keeping the elements of point of view, dialogue, suspense, and theme foremost in your mind. In the end, you will open a window to a room that tells a compelling story.

Choose the Point of View

If a novel is a house and a short story a single room, one of the first things to ask is who is telling the story about the people in that room? Is your story told in first, second, or third person? Notice the different personal pronouns used in each:

- I am in the room. I am the first person.

- You came into the room. You are the second person.

- He or she came into the room. He or she is the third person.

When you select which “person“—first, second, or third—will tell your story, you are deciding on your narrator’s point of view. You’re making a choice about whose eyes the reader will be looking through. First-person and third-person narrators are most commonly used in short stories.

First-Person Point of View

The narrator—often the protagonist—participates in the action and uses the pronouns like I, me, we, and our. This is a good choice for beginning writers because it is easiest to write.

TRUE! —nervous—very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses—not destroyed—not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily—how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

—Edgar Allen Poe, “The Tell-Tale Heart”

Third-Person Point of View

If you elect to use third person, you will choose from one of three possible points of view. Decide which by answering this pivotal question: Do you want your narrator to share the thoughts and feelings of all of the characters, just one of them, or none of them? Consider the following points and examples:

- If you want the narrator to probe into the minds and hearts of all the characters, you will write in the third- person omniscient point of view. You will be able to probe every character’s mind since you will be omniscient or all-knowing. In Charlotte’s Web, E. B. White reveals the feelings of all his characters, including a barnyard pig named Wilbur. When he doesn’t want to eat, the omniscient narrator tells us why.

Wilbur didn’t want food, he wanted love. He wanted a friend—someone who would play with him.

- To reveal the viewpoint of only a single character, use third-person limited. Your narrator can tell what a single “he” or “she” thinks. An author can accomplish a lot by getting into one character’s head. We may feel anything that character feels, see anything that character sees, tastes, smells, senses, or hears. For example, in “Contents of the Dead Man’s Pocket,” author Jack Finney allows us to eavesdrop on the regrets of his protagonist. We are looking in through the window at a man who stands outside his apartment on a ledge eleven stories up—a man very recently driven to succeed. Read his frightening epiphany.

He understood fully that he might actually be going to die; his arms, maintaining his balance on the ledge, were trembling steadily now. And it occurred to him then with all the force of a revelation that, if he fell, all he was ever going to have out of life he would then, abruptly, have had. Nothing, then, could ever be changed; and nothing more—no least experience or pleasure—could ever be added to his life. He wished, then, that he had not allowed his wife to go off by herself tonight—and on similar nights. He thought of all the evenings he had spent away from her, working; and he regretted them. He thought wonderingly of his fierce ambition and of the direction his life had taken; he thought of the hours he’d spent by himself, filling the yellow sheet that had brought him out here. Contents of the dead man’s pockets, he thought with sudden fierce anger, a wasted life.

- If you don’t want to reveal any of your characters’ thoughts, you will use a third-person objective point of view. Your narrator will function like a video camera, recording the action in the room without concern for the thoughts or feelings of the people. Another way to understand the objective point of view is to think of the narrator as a fly on the wall, or in our extended metaphor, a fly on the window. Ernest Hemingway uses this point of view in “Hills like White Elephants.”

The girl stood up and walked to the end of the station. Across, on the other side, were fields of grain and trees along the banks of the Ebro. Far away, beyond the river, were mountains. The shadow of a cloud moved across the field of grain and she saw the river through the trees.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus explains to Scout that “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view . . . until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Writing a short story gives you a chance to share the insight you gained when you walked around in someone’s skin and listened to that other person’s thoughts.

Whether you use first-person or third-person point of view, be consistent and make your narrator reliable. For a comprehensive lesson on the various points of view, read Narrator’s Point of View, which is in Related Resources. When you decide which point of view you want to use in your short story, you should begin to consider what you want your characters to say and how you want them to say it.

Images used in this section: Source: Street-1, Fotograf Myregrund Source: Shannon, Fire monkey fish, Flickr Source: edgar allen poe-tato flakes, Rakka Source: To Kill A Mockingbird, cgauthier2112, Flickr

Figure Out What to Say

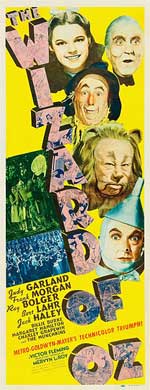

Dialogue, or what characters say, truly makes a lasting impression. You don’t have to be a wizard to name the iconic movie whose characters spoke the memorable lines that follow:

- “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

- “I’ll get you my pretty and your little dog too.”

- “There’s no place like home.”

Just like The Wizard of Oz and nearly all movies, your short story will be more animated and interesting if you include dialogue. Your characters will come to life through their words. Also, dialogue speeds up the action and keeps readers focused. Through dialogue you can, among other things, advance the plot, reveal relationships between characters, share insights, or just have some fun.

Listen to how dialogue enriches these animal encounters in the video below. After you watch it, imagine how it would be without dialogue. This is the magic that also happens when you add thoughtful dialogue to your own characters. O. Henry, who was fond of having dialogue in his short stories, said it was important to “inject a few raisins of conversation into the tasteless dough of life.” K.M. Weiland uses another food metaphor for dialogue, writing “You can think of dialogue as sort of like salt. It perks up the [reader’s] taste buds and makes everything else taste better.”

Paragraph after paragraph of dense text does not appeal to most readers. Remember that each time a character speaks, you start a new paragraph. This mean you can use dialogue to increase the amount of white space on the pages of your story. When you revise your short story, consider how you can season it with dialogue while simultaneously improving its readability. Before you insert dialogue in your short story, however, try this brief, guided practice.

John Hughes’s “Vacation 58” inspired the 1983 comedy movie Vacation. Chevy Chase, as Clark Griswold, drives the family cross-country to “Walley World.” While much of this story is sprinkled with amusing dialogue, the following paragraph is not. Think how you might enliven this leg of the Griswolds’ journey with a few lines of dialogue. The narrator, a kid, sits in the backseat staring at endless rows of corn. What do you think he overhears from the front seat?

Using your notes, script some of the parents’ conversation. When you are finished, check your understanding to see a possible response.

Using your notes, script some of the parents’ conversation. When you are finished, check your understanding to see a possible response.

Mom pleaded with Dad to stop at a motel when we got to Springfield, Illinois. Several times he crossed completely over the median lines and drove in the opposite lane. Once while going through a little town, Dad drove up on the sidewalk and ran over a bike and some toys. Mom accused him of being asleep at the wheel, but he said he was just unfamiliar with Illinois traffic signs.

Now, reread the draft of your own short story. Is there a scene that drags? Is there a character demanding to speak? Was there something you told the reader that you could have shown through lively dialogue? When you add dialogue, skip the small talk like “Hi, how are you?” and get right into real, spirited, and substantive conversation.

Images used in this section:Source: Wizard of Oz 1939 Insert Poster, Cinemamasterpieces, Wikimedia

Source: MR GRISWOLD, Zellaby, Flickr

Suspend Readers in Midair

On May 23, 2012, Nik Wallenda stepped out on a tightrope “suspended” over Niagara Falls, slowly making his way through the mist from the United States to Canada. ABC News was there to catch the action, but since Wallenda was tethered by a safety harness, his highly publicized walk was somewhat anticlimactic. In fact, a far more suspenseful tightrope walk had already occurred in New York almost half a century before. After you finish this section, you’ll be able to watch television footage about the earlier aerialist’s extraordinarily dangerous feat.

When the outcome is certain, viewers tune out, and readers become disengaged. No one expected Wallenda to fail to reach the other side of Niagara Falls. He was a seventh-generation circus performer wearing a safety line. There was a possibility of surprise, but no real surprise. However, suspense will keep readers or viewers more deeply engaged than the distant possibility of surprise. To illustrate the difference between creating surprise and building suspense, we turn to Alfred Hitchcock, the master of suspense.

You and I sit here talking. We’re having a very innocuous conversation about nothing. Boring. Doesn’t mean a thing. Suddenly, boom! A bomb goes off and the audience is shocked—for 15 seconds. Now you change it. Play the same scene, show that a bomb has been placed there, establish that it’s going off at 1 p.m.—it’s now a quarter of one, ten of one—show a clock on the wall, back to the same scene. Now our conversation becomes vital, by its sheer nonsense. Look under the table! You fool! Now the audience is working for 10 minutes, instead of being surprised for 15 seconds.

—Alfred Hitchock

From the beginning of a story, good writers deliberately involve readers by providing clues that foreshadow the ending. With clues, the reader knows more than the main character, becomes invested in the outcome, and anticipates the ending.

Suppose your story is about a tightrope artist taking a skywalk on a high wire suspended between two buildings. What if you mention that, unknown to the aerialist, the far end of the steel cable is beginning to fray? By mentioning the compromised wire, you pose a threat to your protagonist. You heighten the tension by worrying the reader that the aerialist might not reach the other side safely. You’ve created suspense, which has been recognized as an important element in literature as far back as Aristotle. Short story readers are intrigued when writers couple a real sense of danger with a glint of hope that the story will end well.

Thinking of the story you have drafted leading up to this lesson, take the time to consider how to add suspense by sharing something with the reader that your main character doesn’t know. Look at the rising action: Can you provide another hint about the trouble your protagonist will face? Can you insert a realistic detail that will give a clue about the resolution of the story? Can you prolong the climax and keep your reader guessing a while longer?

Naturally, we don’t want to leave you hanging in midair. If the suspense is killing you, you can delay writing your revisions until after you watch the video mentioned at the beginning of this section. Watch as Philippe Petit makes history by traversing a high wire strung between two iconic buildings. Look carefully for his safety harness.

Images used in this section:Source: Nik Wallenda tight rope, canadiantourism, Flickr

Source: Nik Wallenda Walks Across Pittsburgh, jstrak, Flickr

Write about a Central Theme

Stories, novels, plays, and poems, almost always contain a theme or themes. Themes are underlying messages about life and human nature; they are big ideas an author wants to pass on to you. What is tricky about themes is that sometimes they don’t stand out but only emerge after careful analysis. Understanding the theme of a text is an “aha” moment that gives you deeper insight into what an author is trying to say.

As a writer, how do you go about considering theme along with everything else that’s involved in writing a short story? Let’s begin by saying that theme is an important part of your short story planning process. Themes are the abstract concepts or universal truths found in all good literature. Themes are born out of an author’s observation about the human condition. The writer communicates those observations through the characters in the story. The changes your characters make as they progress through the story will help you define your theme.

Read the story below and think about how you would answer these three questions:

- What is the main character’s internal conflict?

- Which of the main character’s views and attitudes will change as a result of the story’s events? How and why?

- How does the main character demonstrate those changed views and attitudes at the beginning and the end of the story?

The Fish and the Salamander

At the beginning of time, Fish and Salamander looked very much alike. They were discussing how they planned to evolve.

“I wish to grow thinner and to grow my tail broad,” said Fish. “Then I will swim like lightning and outrace any creature in the pond. How about you?”

Salamander considered. “Well, it would certainly be nice to be the fastest creature in the pond. But I think I will keep my awkward tail, which allows me to swim well enough. What I wish to change instead is to grow some modest legs.”

Fish laughed. “Legs? In a pond? What a waste!”

Soon, though, came a drought, and the pond began to dry up. Fish was trapped, but Salamander was able to crawl out in hopes of finding another pond.

“How did you know that legs would come in so handy?” cried Fish to his departing friend.

“I didn’t,” said Salamander. “But I wasn’t so naive as to assume that circumstances today would be the same as circumstances tomorrow.”

Would you say that the internal conflicts of the characters are their respective decisions about how to change their bodies? Fish seems to change at the end of the story as he realizes the error of his decision when he asks Salamander why he knew the right decision to make.

We know that Fish changes or is forced to change by the circumstances of nature.

Finally, we can answer question number three by showing Fish’s arrogance in the face of Salamander’s logic and forethought. We see Fish’s arrogance disappear as he “cries” to Salamander for an explanation as to Salamander’s wise choice.

Even though this is a very short story with a simple plot and only two characters, we can have a discussion about the “human” condition that informs the story—the theme of this story.

As you continue thinking about your short story remember the following:

The secret of theme lies entirely in the hands of your characters. As with almost every other aspect of story, character is the vital key to making your theme come to unforgettable life.

—K. M. Weiland, “Crafting Unforgettable Characters”

You’re nearing the end of this trio of lessons on how to write a short story. You may have been writing with a theme in mind, but if you’re unsure about theme, you might want to review the lesson “Analyzing Various Texts with Similar Themes.” To get to know your own theme better, ask yourself a few questions: What was your purpose in writing this story? What central insight or universal truth did you want to convey? What truth did you discover as you were writing?

As with anything worth doing, writing an interesting short story takes time and patience. As you continue to practice, your characters will come alive and themes will take shape from their actions.

Images used in this section:Source: FiestaTexas4, Rei, Wikimedia

Source: Coryphopterus glaucofraenum, LASZLO ILYES, Wikimedia

Source: Salamander larve, Simbyte

Read "A Retrieved Reformation" (Part 3)

The ending of a short story should satisfy readers and make them feel that the effort of reading to the finish was worth it. Few writers deliver endings that are more satisfactory than O. Henry’s. If you read the earlier lessons on writing, you may recall that in Part 2 of “A Retrieved Reformation,” Jimmy fell in love with the banker’s daughter in Elmore, Arkansas. This love was so transformative for the protagonist that he became willing to go straight, even though going straight meant parting with his prized suitcase of safecracking tools. Before he could send the heavy suitcase to a former “colleague,” however, a five-year-old girl got locked inside Elmore Bank’s foolproof vault by accident.

Read this last section to find out how Jimmy deals with this crisis. Click the link to open an excerpt from “A Retrieved Reformation” by O. Henry. When you’re finished reading the document, return to this section.

William Sidney Porter took the pen name of O. Henry because he had a criminal record. What pseudonym would you take to conceal your identity? Hopefully the short story you have been working on will be good enough to submit under the name your parents gave you. Before you begin your final revision, answer these questions about “A Retrieved Reformation” to review the literary strategies discussed in this lesson. Click on the best answer for each question.

Images used in this section:Source: Gangster look, Kevins’ Collections, Flickr

Finish Your Story

“Automobile warranty expires. So does engine.”

In the succinct story above by Stan Lee, just what you expect is what happens. However, what happens in “A Retrieved Reformation” is the opposite of what you expect. Your tale, predictable or not, must come to an end. Use the rubric below to assess your current draft. After that, your final task is to revise your work, keeping in mind plot, character, theme, and the literary strategies addressed in the three lessons. You can even use the point system included to score your own draft. Good luck!

Literary Terms/Elements 30

- Literary elements, including suspense and dialogue, enhance the story.

Characters 10

- Characters are interesting and believable (5pts).

- Both direct and indirect characterization are used to create well-developed characters (5 pts).

Plot 50

- All parts are written well and add to the story:

- Exposition sets the scene and introduces the characters while also hooking the reader (10 pts).

- The critical incident and rising action build the plot and deepen reader understanding of the characters and the story (8 pts).

- Climax is the height of tension and makes the reader wonder what will happen next (8 pts).

- Falling action shows effects of the climax and leads toward the resolution (8 pts).

- Resolution ties up all of the loose ends and/or might introduce a new conflict (8 pts).

- A theme is evident from the story and appropriate to the characters and plot (8 pts).

Written Conventions 10

- Spelling, punctuation, and grammar are generally correct with few mistakes (5pts).

- Language is appropriate for the story and audience (5 pts).

Total

____/100

Images used in this section:Source: Junkyard 1, squarejer, Flickr

Resources

Bailey, Tom. A Short Story Writer’s Companion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Barancik, Steve. “The Fish and the Salamander.“ Best-childrens-books.com.

//www.best-childrens-books.com/modern-fables-for-children.html#fish-and-salamander.†

CBS News. “Tightrope Walk Across World Trade Center (1974).” YouTube video, 2:11. Posted Dec 27, 2008.

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAVj2IVC9ko.

“English Proverbs.” The Phrase Finder. //www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/proverbs.html.

Finney, Jack. “Contents of the Dead Man’s Pocket.” Wayne State University.

//www.is.wayne.edu/mnissani/20302005/Deadman.htm.

Gavan, Cara. “Using the Genre Approach to Teaching Suspense Short Story Writing.” SUNY Cortland.

//facultyweb.cortland.edu/kennedym/genre%20studies/sssuspense.htm.

Gioia, Dana and R.S. Gywnn, eds. The Art of the Short Story. New York: Pearson Longman, 2006.

Hemingway, Ernest. “Hills like White Elephants.”

//faculty.weber.edu/jyoung/English%202500/Readings%20for%20English%202500/Hills%20Like%20White%20Elephants.pdf.

Henry, O. “A Retrieved Reformation.” In Roads of Destiny. Project Gutenberg. February 5, 2006.

//www.gutenberg.org/files/1646/1646-h/1646-h.htm#10.

Holland, Bruce. “You’ll Know It When You See It.” Flash Fiction Online, (blog).

//www.flashfictiononline.com/c20080603-youll-know-it-when-you-see-it-bruce-holland-rogers.html.

Hughes, John. “Vacation 58.” Zoetrope 12, no. 2 (Summer 2008).

Humpage, A. J. “Creating Suspense in Fiction.” All Write — Fiction Advice (blog). June 4, 2011.

//allwritefictionadvice.blogspot.com/2011/06/creating-suspense-in-fiction.html.

Lee, Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird. First Perennial Classic ed. New York: HarperPerennial, 2002.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Classic Literature. About.com.

//classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/eapoe/bl-eapoe-telltale.htm.

Sullivan, Frank. “The Night The Old Nostalgia Burned Down.” New Yorker, May 25, 1946.

Thomson, Amy Restivo. “Elemental Fiction.” Trinity University. August 1, 2011.

//digitalcommons.trinity.edu/educ_understandings/162.

Weiland, K.M. Crafting Unforgettable Characters. KMWeiland.com. E-book.

//www.kmweiland.com/wp-content/uploads/crafting-unforgettable-characters.pdf .

White, E. B. Charlotte’s Web. New York: HarperTrophy, 1980.

†Republished with permission from Steve Barancik, Best Children’s Books