Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define nuclear fusion

- Discuss processes to achieve practical fusion energy generation

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

- 1.C.4.1 The student is able to articulate the reasons that the theory of conservation of mass was replaced by the theory of conservation of mass-energy. (S.P. 6.3)

- 4.C.4.1 The student is able to apply mathematical routines to describe the relationship between mass and energy and apply this concept across domains of scale. (S.P. 2.2, 2.3, 7.2)

- 5.B.11.1 The student is able to apply conservation of mass and conservation of energy concepts to a natural phenomenon and use the equation to make a related calculation. (S.P. 2.2, 7.2)

- 5.G.1.1 The student is able to apply conservation of nucleon number and conservation of electric charge to make predictions about nuclear reactions and decays such as fission, fusion, alpha decay, beta decay, or gamma decay. (S.P. 6.4)

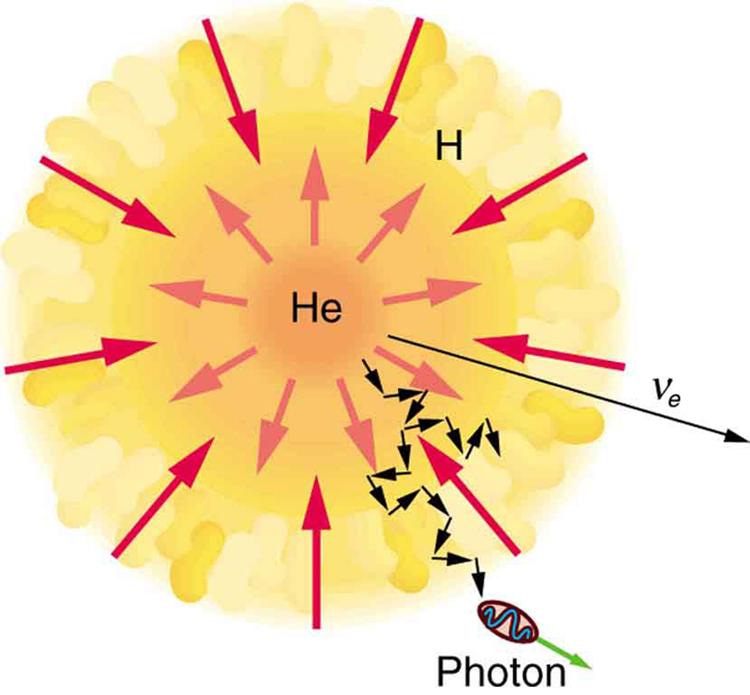

While basking in the warmth of the summer sun, a student reads of the latest breakthrough in achieving sustained thermonuclear power and vaguely recalls hearing about the cold fusion controversy. The three are connected. The sun's energy is produced by nuclear fusion (see Figure 15.10). Thermonuclear power is the name given to the use of controlled nuclear fusion as an energy source. While research in the area of thermonuclear power is progressing, high temperatures and containment difficulties remain. The cold fusion controversy centered around unsubstantiated claims of practical fusion power at room temperatures.

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two nuclei are combined, or fused, to form a larger nucleus. We know that all nuclei have less mass than the sum of the masses of the protons and neutrons that form them. The missing mass times equals the binding energy of the nucleus—the greater the binding energy, the greater the missing mass. We also know that the binding energy per nucleon, is greater for medium-mass nuclei and has a maximum at Fe (iron). This means that if two low-mass nuclei can be fused together to form a larger nucleus, energy can be released. The larger nucleus has a greater binding energy and less mass per nucleon than the two that combined. Thus mass is destroyed in the fusion reaction, and energy is released (see Figure 15.11). On average, fusion of low-mass nuclei releases energy, but the details depend on the actual nuclides involved.

The major obstruction to fusion is the Coulomb repulsion between nuclei. Since the attractive nuclear force that can fuse nuclei together is short ranged, the repulsion of like positive charges must be overcome to get nuclei close enough to induce fusion. Figure 15.12 shows an approximate graph of the potential energy between two nuclei as a function of the distance between their centers. The graph is analogous to a hill with a well in its center. A ball rolled from the right must have enough kinetic energy to get over the hump before it falls into the deeper well with a net gain in energy. So it is with fusion. If the nuclei are given enough kinetic energy to overcome the electric potential energy due to repulsion, then they can combine, release energy, and fall into a deep well. One way to accomplish this is to heat fusion fuel to high temperatures so that the kinetic energy of thermal motion is sufficient to get the nuclei together.

You might think that, in the core of our sun, nuclei are coming into contact and fusing. However, in fact, temperatures on the order of are needed to actually get the nuclei in contact, exceeding the core temperature of the sun. Quantum mechanical tunneling is what makes fusion in the sun possible, and tunneling is an important process in most other practical applications of fusion, too. Since the probability of tunneling is extremely sensitive to barrier height and width, increasing the temperature greatly increases the rate of fusion. The closer reactants get to one another, the more likely they are to fuse (see Figure 15.13). Thus most fusion in the sun and other stars takes place at their centers, where temperatures are highest. Moreover, high temperature is needed for thermonuclear power to be a practical source of energy.

The sun produces energy by fusing protons or hydrogen nuclei (by far the sun's most abundant nuclide) into helium nuclei The principal sequence of fusion reactions forms what is called the proton-proton cycle:

where stands for a positron and is an electron neutrino. (The energy in parentheses is released by the reaction.) Note that the first two reactions must occur twice for the third to be possible, so that the cycle consumes six protons () but gives back two. Furthermore, the two positrons produced will find two electrons and annihilate to form four more rays, for a total of six. The overall effect of the cycle is thus

where the 26.7 MeV includes the annihilation energy of the positrons and electrons and is distributed among all the reaction products. The solar interior is dense, and the reactions occur deep in the sun where temperatures are highest. It takes about 32,000 years for the energy to diffuse to the surface and radiate away. However, the neutrinos escape the sun in less than two seconds, carrying their energy with them, because they interact so weakly that the sun is transparent to them. Negative feedback in the sun acts as a thermostat to regulate the overall energy output. For instance, if the interior of the sun becomes hotter than normal, the reaction rate increases, producing energy that expands the interior. This cools it and lowers the reaction rate. Conversely, if the interior becomes too cool, it contracts, increasing the temperature and reaction rate (see Figure 15.14). Stars like the sun are stable for billions of years, until a significant fraction of their hydrogen has been depleted. What happens then is discussed in Introduction to Frontiers of Physics.

Theories of the proton-proton cycle (and other energy-producing cycles in stars) were pioneered by the German-born, American physicist Hans Bethe (1906–2005), starting in 1938. He was awarded the 1967 Nobel Prize in physics for this work, and he has made many other contributions to physics and society. Neutrinos produced in these cycles escape so readily that they provide us an excellent means to test these theories and study stellar interiors. Detectors have been constructed and operated for more than four decades now to measure solar neutrinos (see Figure 15.15). Although solar neutrinos are detected and neutrinos were observed from Supernova 1987A (Figure 15.16), too few solar neutrinos were observed to be consistent with predictions of solar energy production. After many years, this solar neutrino problem was resolved with a blend of theory and experiment that showed that the neutrino does indeed have mass. It was also found that there are three types of neutrinos, each associated with a different type of nuclear decay.

The proton-proton cycle is not a practical source of energy on Earth, in spite of the great abundance of hydrogen ). The reaction has a very low probability of occurring. This is why our sun will last for about 10 billion years. However, a number of other fusion reactions are easier to induce. Among them are the following:

Deuterium is about 0.015 percent of natural hydrogen, so there is an immense amount of it in sea water alone. In addition to an abundance of deuterium fuel, these fusion reactions produce large energies per reaction (in parentheses), but they do not produce much radioactive waste. Tritium is radioactive, but it is consumed as a fuel (the reaction and the neutrons and can be shielded. The neutrons produced can also be used to create more energy and fuel in reactions like

and

Note that these last two reactions, and put most of their energy output into the ray, and such energy is difficult to utilize.

The three keys to practical fusion energy generation are to achieve the temperatures necessary to make the reactions likely, to raise the density of the fuel, and to confine it long enough to produce large amounts of energy. These three factors—temperature, density, and time—complement one another, and so a deficiency in one can be compensated for by the others. Ignition is defined to occur when the reactions produce enough energy to be self-sustaining after external energy input is cut off. This goal, which must be reached before commercial plants can be a reality, has not been achieved. Another milestone, called break-even, occurs when the fusion power produced equals the heating power input. Break-even has nearly been reached and gives hope that ignition and commercial plants may become a reality in a few decades.

Two techniques have shown considerable promise. The first of these is called magnetic confinement and uses the property that charged particles have difficulty crossing magnetic field lines. The tokamak, shown in Figure 15.17, has shown particular promise. The tokamak's toroidal coil confines charged particles into a circular path with a helical twist due to the circulating ions themselves. In 1995, the Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor at Princeton in the United States achieved world-record plasma temperatures as high as 500 million degrees Celsius. This facility operated between 1982 and 1997. A joint international effort is underway in France to build a tokamak-type reactor that will be the stepping stone to commercial power. ITER, as it is called, will be a full-scale device that aims to demonstrate the feasibility of fusion energy. It will generate 500 MW of power for extended periods of time and will achieve break-even conditions. It will study plasmas in conditions similar to those expected in a fusion power plant. Completion is scheduled for 2018.

The second promising technique aims multiple lasers at tiny fuel pellets filled with a mixture of deuterium and tritium. Huge power input heats the fuel, evaporating the confining pellet and crushing the fuel to high density with the expanding hot plasma produced. This technique is called inertial confinement, because the fuel's inertia prevents it from escaping before significant fusion can take place. Higher densities have been reached than with tokamaks, but with smaller confinement times. In 2009, the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory (CA) completed a laser fusion device with 192 ultraviolet laser beams that are focused upon a D-T pellet (see Figure 15.18).

Example 15.2 Calculating Energy and Power from Fusion

(a) Calculate the energy released by the fusion of a 1.00-kg mixture of deuterium and tritium, which produces helium. There are equal numbers of deuterium and tritium nuclei in the mixture.

(b) If this takes place continuously over a period of a year, what is the average power output?

Strategy

According to the energy per reaction is 17.59 MeV. To find the total energy released, we must find the number of deuterium and tritium atoms in a kilogram. Deuterium has an atomic mass of about 2 and tritium has an atomic mass of about 3, for a total of about 5 g per mole of reactants or about 200 mol in 1.00 kg. To get a more precise figure, we will use the atomic masses from Appendix A. The power output is best expressed in watts, and so the energy output needs to be calculated in joules and then divided by the number of seconds in a year.

Solution for (a)

The atomic mass of deuterium is 2.014102 u, while that of tritium is 3.016049 u, for a total of 5.032151 u per reaction. So a mole of reactants has a mass of 5.03 g, and in 1.00 kg there are The number of reactions that take place is therefore

The total energy output is the number of reactions times the energy per reaction.

Solution for (b)

Power is energy per unit time. One year has so

Discussion

By now we expect nuclear processes to yield large amounts of energy, and we are not disappointed here. The energy output of from fusing 1.00 kg of deuterium and tritium is equivalent to 2.6 million gallons of gasoline and about eight times the energy output of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Yet the average backyard swimming pool has about 6 kg of deuterium in it, so that fuel is plentiful if it can be utilized in a controlled manner. The average power output over a year is more than 10 MW, impressive but a bit small for a commercial power plant. About 32 times this power output would allow generation of 100 MW of electricity, assuming an efficiency of one-third in converting the fusion energy to electrical energy.